![]()

“A Hidden Life”, a chronicle of a conscientious objector during the rise of the Third Reich, is Terrence Malick’s most challenging and dreary film to date. This time around his narrative is more focused than his recent experiments such as “Song to Song” and “Knight of Cups”, and while the picture is indeed flawed, it is still epic in scope with a grueling running time of nearly three hours. The film almost comes off like a spiritual swan song like Lars von Trier’s “The House that Jack Built” or even Martin Scorsese’s films “Silence” and “The Irishman”. The film plays out like a greatest hits compilation as it uses collages of imagery and scenes that mirror his earlier masterpieces like “Badlands” and “Days of Heaven”. Malick still continues his quick-cut, swirling montage style that he has used since his 2005 masterpiece “The New World”, but sadly, the style has grown mundane and “A Hidden Life”, while more cohesive and determined than his previous films, still suffers from self-parody.

Malick’s framework has always consisted of his characters struggling with the purpose of their own existence. Whether on a literal, subconscious, or even unconscious dreamlike level, he questions what guides them to where they are. By using visual motifs along with a fragmented collage of steadi-cam moving images and poetic voice-over narration, Malick’s films always come across as if you are visiting the mind of someone else: their thoughts, memories, and recollections time and experiences. Malick’s latest film uses the same techniques as it becomes a study of courage; a film addressing the moral conundrums inherent to resisting conformity that takes a strong side of liberty over totalitarianism. It is rather a study of how tyranny not only destroys societies, but how it destroys the mind, heart, and soul.

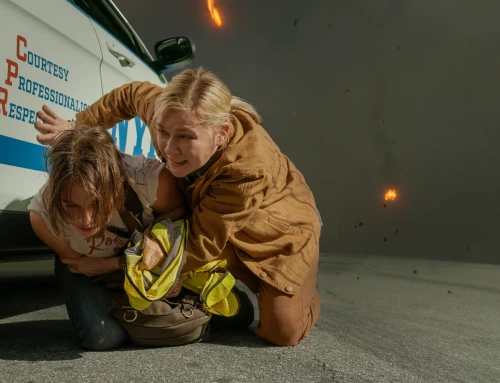

(Photo: Fox Searchlight Pictures)

The film examines the life of Franz Jagersatter (August Diehl), a conscientious objector that truly believes in the principles of non-aggression. Franz is an introverted, timid, quiet man who is a practicing Catholic that refuses to take the oath to Adolf Hitler, fight on the battle front, or serve in the Nazi army. Franz ends up facing deep persecution and even risking imprisonment by resisting the Nazi government.

Malick’s “A Hidden Life” becomes a contemplative study of courage that quickly dissolves into internal conflict about a man seeing him lose his country and faith in God. As Franz witnesses his country slip away to a dangerous totalitarianism as his nation’s values continue to shift very dangerously, he even sees his place of worship conforming to the state, leading him to question the church’s ethics and his own purpose.

Set in a small Austrian village surrounded by ravishing green hills, streams creeks, forest fog, farm animals, and luminous cornfields, the camera glides in typical Malickian fashion through the geographical vicinity. These images aren’t designed to feel heavenly or spiritually uplifting; rather, they serve as a caution in how moments in time can be peaceful and tame, and shortly thereafter disrupt into unbalance and despair.

This marks the first historical epic Malick has approached since his 2005 masterpiece “The New World”. The film starts off in 1939–a newsreel montage reveals Hitler’s rise to power. Franz lives with his wife Franzika (Valernie Pancher), and they have a family together of young daughters as they farm, cut fields, attend to the farm animals, and grow livestock. Once he is called up in 1943, after Germany has conquered and occupied several nations that has led to millions of deaths. Franz refuses to partake in Hitler’s regime that is based on war, genocide, and conquest.

Malick examines the complexities and hardships Franz’s principles bring to him, which could lead him to being imprisoned, punished, tortured, and possibly even sentenced to death for “treason”. Franz’s staunch principles will also lead to his dislocation and disconnection from Franzika and his daughters, and his refusal can lead to his family being shunned by their community who conform to Hitler’s cult of personality. These are consequences that open up deep philosophies about complicity and conformity in society and just how easy it is for people to be apathetic or just surrender to the power of the state.

“A Hidden Life” becomes more than just a film about a noble farmer resisting Nazis. A far inferior film would use this as a way for the filmmaker and viewer to feel morally superior. Malick is more interested in building up deep moral conundrums and ambiguities here. Malick profoundly asks just how far one can take their principles before they cave into conformity. How can one truly practice the principles of non-aggression and resisting coercion if their own resistance is causing harm on others—including their own family and loved ones? What defines courage, and can courage slip into cowardice? Is self-preservation noble if it brings harm to others? These are all deep philosophical and moral ambiguities that prove just how thoughtful of an auteur Terrence Malick is.

To his credit, August Diehl—who played a Nazi soldier in Quentin Tarantino’s 2009 masterpiece “Inglorious Basterds”—delivers a commanding performance filled with great expressionism that is minimal in dialogue. His performance brings deep affection and several conflicting tones. Malick brings great compassion and empathy to the characterization and internal torment of Franz. There is a supporting cast that consists of the late Bruno Ganz, Michael Nyqvist, and Matthias Schoenaerts, all of whom deliver notable and critical small roles.

“A Hidden Life” all around remains a minor offering in Malick’s oeuvre; his artfulness is indeed getting monotonous–how many times can we see a camera twirl as characters narrate and gaze out at a field? Sadly, Malick continues to descend into self-parody. While “A Hidden Life” feels more observant and cohesive than his last few films, it would be liberating to see Malick abandon the montage style and minimalism entirely and do a more cohesive framework one last time. Ultimately, the film stretches itself longer than it should during the middle section, yet it never feels too self-indulgent and the film’s first hour is indeed extraordinary and a reassurance that he is a deeply committed filmmaker that is never timid in asking uncomfortable questions about humanity’s existence.

Saw it last week, still very lukewarm about it. I think I am done with Malick unless his next film as you mentioned above is completely different. I just don’t think he has the interest in making something more unique, he is too comfortable and beholden to this montage style.

There is something very meandering about this film that just didn’t work for me.

I adored this film. It is so relevant to our times and is Malick’s masterpiece

Saw A Hidden Life today. Would’ve made for a fascinating documentary, however it felt rather pretentious and meandering for a majority of the film for me.

The performances of the leads was so moving. I hope the real people’s love was as wonderful as it was depicted by the actors. It was so real… so palpable to me.

Thanks so much for sharing this awesome info! I am looking forward to see more postsby you!

Heya! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any problems with

hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing several weeks of hard

work due to no back up. Do you have any methods to protect against hackers?

adreamoftrains website hosting

This site truly has all of the information and facts I needed about this subject and didn’t know who

to ask.

I know this site provides quality dependent articles or reviews and extra material, is there

any other web page which presents these data in quality?

My relatives always say that I am wasting my time here at

web, however I know I am getting know-how everyday

by reading such good articles or reviews.

Saved as a favorite, I love your blog!

Thankfulness to my father who told me about this web site, this website is actually remarkable.|